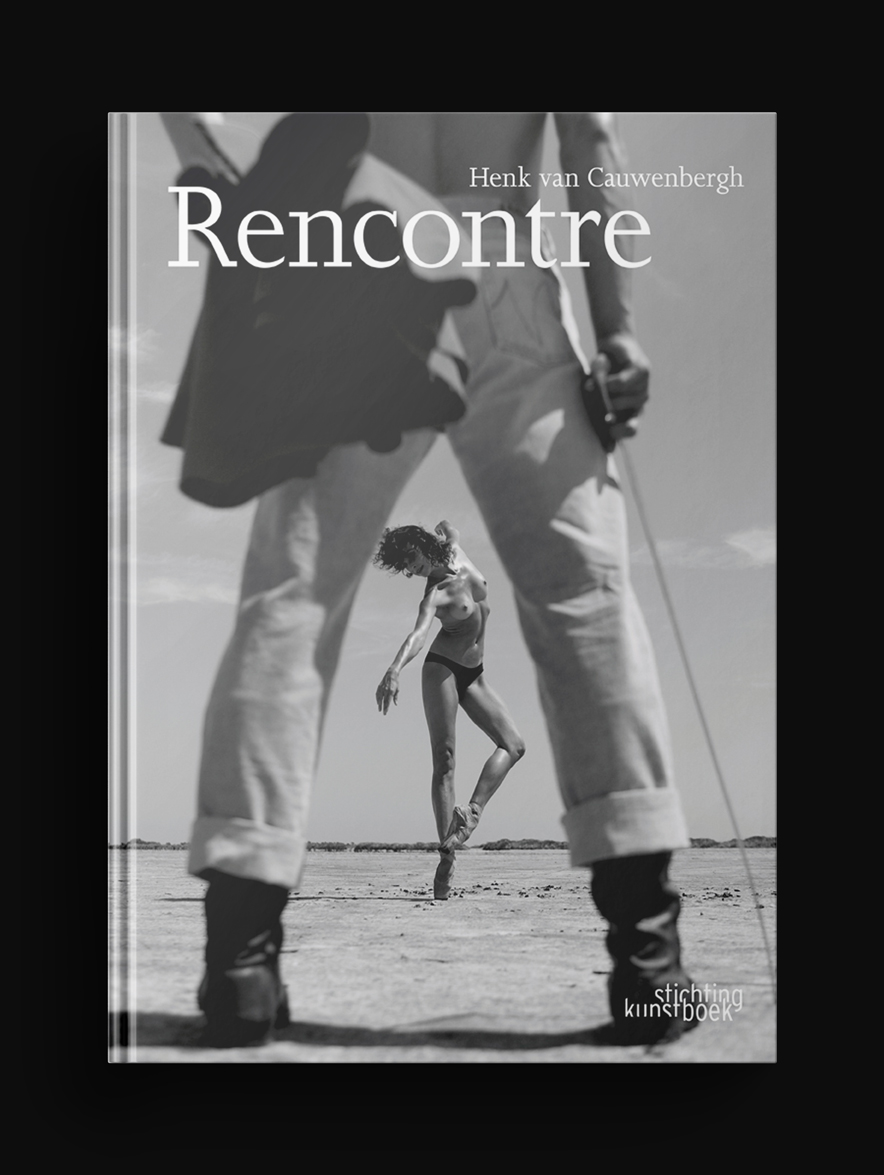

For the attentive viewer who witnesses, for example, an outstanding dance performance, the term ‘movement’ can take on a new meaning. The combinations of grace and power, of stamina and lucidity, of playfulness and control free the complex of senses, nerves and muscles from its everydayness and elevate movement to that level of virtuosity inherent to what we call art.

It is not always clear to that same viewer that such free control of movement is the result of a lengthy, highly demanding and sometimes even merciless training process. When I had the privilege of seeing the première of the photos in Rencontre, what immediately struck me were the focus and earnestness with which both athletes prepare themselves with an eye to their performance.

From sport we know that most athletes must complete at least 10,000 hours of training before they can take a stab at getting to the top.

Hours, days, weeks and years of continual engagement and training are required before an athlete can achieve such a level of control. Though there are examples illustrating that natural ability plays a very significant role, a well-conceived training process provides an opportunity for full development of this ability.

A wide range of physiological, biomechanical, psychological and neurological processes develop during this efficient preparation, which in turn result in the ultimate performance.

Much more than an homage to the body, this training period on the way to the top is a test that separates the wheat from the chaff.

I recently visited the sports surgery hospital of a friend and colleague in Cape Town, South Africa during the World Cup. At the entry to the exercise room where many an Olympic champion has been formed, three quotes were hanging which I found reflected in Rencontre as well.

Courage is the spirit that demands the impossible.

The courage to outdo yourself, as well as the sacrifices that you must make to do so, can be seen as a repetitive constant in the piercing gaze of both athletes. The phenomenal stretching of the hamstrings in the ballerina and the muscular mismatch between the anterior and posterior muscle groups around the toreador’s shoulders bear witness to this. Or the pronounced lumbal lordosis in her and the axial elasticity in him.

This clearly establishes how a body can ultimately be tuned to the needs of the effort which is required.

Risk is the foundation of ultimate reward.

It demands a high form of control to dance while leaping en pointe in front of a full ballet theatre, or to stand eye to eye with a snorting and unpredictable bull.

There is no success without hardship.

Behind the ballerina’s idyllic tutu and other accoutrements are a body and feet that tell a story of injury and strain, evidence of the most rigorous training.

The brazen costume of the toreador contains a body that displays the distinct traces of the intensity and specificity of his physical training.

It is just as coincidental for a top photographer to meet a sports surgeon as for a ballerina from Monaco to venture into a toreador’s sandy corrida. And yet I can see some clear parallels: the focus on preparation, the control during performance, the anticipation of the body tone and unrelenting drive it takes to aspire to a higher level until complexity ascends to simplicity.

In this way I also have become a great admirer of Henk van Cauwenbergh’s work. In addition to the quality of the photography, each picture has a story behind it, and behind each view there is a an extrapolation of Henk’s personality, which I hold in the highest esteem.

This series of photographs captures the dynamics between these two very different top athletes in such a beautiful way that you can almost taste in the grand and mysterious décor of the Camargue the salty scent of the water all around.

And it is for this very reason that Henk elevates this meeting to the level of art…

Pieter D’Hooghe